|

Verities: Raising Ammama |

|

|

by Elizabeth Stanard

My first encounter with high art was on my hands and knees. During one rainy hide-and-seek afternoon, I attempted to scrooch under my parents' bed before I was sought, only to nose into an arcane art barnacle barring my entry.

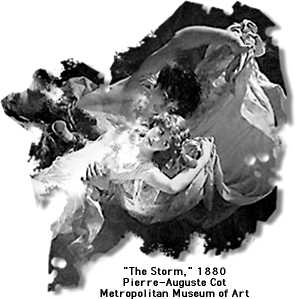

Vaunting the dimensions of a queen-sized mattress, "The Storm" was a marvel to my young eyes when it was later revealed. And MY great-grandmother, my Mama's mama's mama, had replicated this masterpiece, an oil painting by

"Ammama studied art in New York," my parents boasted. "Her name was Elizabeth too, and you'll be an artist like she was." Unfortunately, this mantra was basically the extent of Ammama's limelight in the familial oral herstory; but, through its repetition, I soon began realizing its augury.

As genetics would have it, I inherited my great-grandmother's ability not only to draw but also to successfully plagiarize. At age 8, I won a whopping, cheek-blushing $25 for landing first place in the city-wide fire prevention poster contest by employing the same octopus-holding-eight-fire-hazards concept as my mother had thirty years before.

My childhood career as a visual artist was well on its way. Art lessons. Art camp. Art enrichment programs. And my favorite, art projects at home in The Art Room: the dark room bonus that my parents had acquired when purchasing the house, the cocktail party anecdote that was of no value but for that of mere entertainment, the glorified closet that permitted and contained the messes.

I remember the Crayola Caddy. And the markers that smelled like lemons and blueberries and cinnamon. And the smocks that had been demoted from my dad's shirt closet. And always pronouncing kiln as kill. And saturating paper with dripping watercolor paints. And never, ever forgetting to color in the sky.

When adolescence began to encroach on my childhood, the inundant conflation of teenage demands vied for any time I might have otherwise devoted to visual arts; although I still managed to design propaganda for my extracurricular activities and doodle in my drawing classes.

In college, I smattered in drawing and design classes to determine if sketching on a Strathmore pad still evoked those creative scintillations. Yes, sometimes. But more often than not, translating my visual aesthetic onto paper had become an exercise of automation in which I was merely a vessel through which my genetic inclinations passed.

Now ten years later, now that I have donated my PrismaColors to old roommates and 9 year-olds, I make an effort to at least visit art museums and galleries occasionally. And just more than occasionally, after unsuccessfully navigating through these labyrinths of sterility with a chronic disorientation, I happen upon a rectangle of art that arrests my petulant feet.

Recently I found myself at the Met, captivated by "The Storm" for a second time. Sitting Indian-Style on the floor, shamelessly incepting and venerating its glory, I chilled at what art could be and winced at what mine was not. No, I was not going to be a fireman or a nurse or an astronaut after all.

But before long, I began conversing with the creation. I invited it to unravel my tightly coiled phrases with silliness and wonder, to splinter and lube my sentence temples with its humid midnight air. It pulped and blended my poetic musings, pounded them into words that curved and frolicked into its lappets of emotion. Its luminous figures, simultaneously escaping and confronting parlous unknowns, conjured crisp dots of prose, poignant despite the wooden frame.

Yes, Saturday game-goers, that tribal paint, red and white or blue and gold, applied with her fresh manicured nails, glosses ecstasy near the depths of your white beer-belly buttons.

The visual, in all of its incarnations, be it written, baked or gauchely applied, is art.

So now Ammama, somebody's mama.......can you see past me free?

|

||

top | this issue | ADA home |

||