|

Notes from the Woodshed |

|

|

by Paul Klemperer

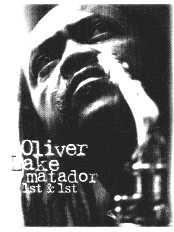

Oliver Lake: A Voice Spanning Generations

Even though "free jazz" appeared on the scene almost forty years ago and is recognized around the world as an important part of the jazz tradition, for many listeners it still conjures up images of cacophony and abrasive noise. Fans of more traditional jazz frequently equate the term "free" with "structureless." This leads to a range of misinterpretations of the music, with the general result that free jazz is artificially isolated from the rest of the jazz tradition.

Instead, it is helpful to remember that jazz is an expressive process; while compositions and recordings may be fixed in time, the trajectory of jazz is in movement. Just look at how quickly the music has evolved and branched out in the course of one century.

Many musicians feel the term "jazz" is limiting and eschew it for more descriptive terms like "improvistional music" or "creative music." They feel that the music has grown beyond the historical boundaries implied by the term "jazz." Practitioners of free jazz put this philosophy into practice, not by ignoring the musical structures of the jazz tradition but by transcending them through the spontaneous referencing of various parts of that tradition, creating a "spontaneous structure" in the moment of performance. Since jazz continues to evolve, incorporating elements from all the world's musics, free jazz theoretically has no limits except those of the individual performers.

Oliver Lake is one of the more prolific artists, known best for his work on alto saxophone, but with a history of mixed media performance. He has appeared on the recordings of many other musical pioneers, including drummer Andrew Cyrille, bassist Reggie Workman, guitarist A. Spencer Barefield, and members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music (AACM), just to name a few.

Explorations in free jazz in the 1960s paralleled the rising Black Consciousness movement, and the advocacy of freedom and self-determination in all areas of life. With this advocacy came a heightened awareness of African history and traditions. Music scholars began to dig deeper into the African cultural traditions, which have been a source of strength and inspiration for African American music, both through specific musical practices and more general aesthetic parameters.

For African American artists, the African aesthetic looks both to the past and the future. Learning and preserving traditional arts does not preclude experimentation and discovery, but reaffirms the underlying unity behind new explorations in music, dance, poetry and all the arts. For audiences to these explorations, it is helpful to have an awareness of the historical and aesthetic issues involved, particularly when the term "free" is invoked. This is especially true with regard to the work of Oliver Lake.

Lake's musical influences are complex and far-reaching. His intense and intimate energy creates a direct bond with audiences, but he simultaneously digs deep into the jazz tradition. The Penguin Guide To Jazz describes his style as containing "a sort of convulsive beauty that requires a little time to assimilate." There are connections to Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, and the free jazz proponents of the 1960s, as well as the New York loft scene of the 1970s, and various avant-garde forays into the areas of funk and world beat (anticipating "acid" jazz by at least a decade). His musical voice spans generations, incorporating elements from across his wide-ranging artistic experience.

Lake's interest in mixed media performance, particularly music with spoken word, goes back to the 1960s. "I began writing and reciting poetry in the late '60s as a founding member of the multi-disciplined Black Artist Group in St. Louis, Missouri," he explains." He moved to New York City in the 1970s, continuing his work with poets, Ntozake Shange being the most notable. There he wrote a multimedia theater piece called Life Dance Of Is, incorporating music, dance and poetry. This work was performed in the late '70s in New York and Washington, D.C.

In 1977 Lake co-founded the World Saxophone Quartet, which is known for its free-wheeling explorations into various jazz-related genres such as R&B, New Orleans second line, ragtime, funk, and West African pop, often with a humorous and ironic approach to the material. Over the years the WSQ collective has included other modern reed luminaries such as David Murray, Julius Hemphill and Hamiet Bluiett, all of whom have demonstrated a deep-rooted versatility with the jazz tradition.

For those more familiar with Oliver Lake's work in the context of the WSQ and other collectives, his Matador show is a wonderful opportunity to appreciate Lake's charismatic use of ritual space.

"Taking the stage solo can be frightening. The performer must stay focused throughout, and have fun. This is a challenge and a complete and natural high."

Oliver Lake performs with a multi-levelled expressiveness, evoking the revolutionary aggressiveness of '60s free jazz, the attention to texture and space of spoken word performance, the power and rhythm of dance music, the ironic humor of social commentary. He weaves these elements together in a performance ritual that is both new and very old, equal parts space-age explorer and African storyteller.

|

||

top | this issue | ADA home |

||

Lake's recent one-man show, The Matador of 1st & 1st, draws on his musical and dramatic abilities, interspersing melodic outbursts on sax and flute with poetry, chant and song. "I like to think of the poet as storyteller, as The Matador, telling my life -- storytelling as an African tradition. Playing an instrument is one way of communicating with the audience, but using the voice is the most direct."

Lake's recent one-man show, The Matador of 1st & 1st, draws on his musical and dramatic abilities, interspersing melodic outbursts on sax and flute with poetry, chant and song. "I like to think of the poet as storyteller, as The Matador, telling my life -- storytelling as an African tradition. Playing an instrument is one way of communicating with the audience, but using the voice is the most direct."